China: Corporate Learning Outlook

Key corporate learning points

- Despite rising authoritarianism and protectionism China remains key to investors’ global growth strategies

- Service sector growth and economic stabilisation helped China hit its 2016 GDP growth target, but expansionary policies might undermine structural reforms

- Investors should carefully monitor complex legal and regulatory changes that are being implemented inconsistently at local level

- Business-friendly tax and labour reforms are slow to show benefits requiring companies to be patient

China ‘is cracking down, closing up, and lashing out in ways different from its course in the previous 30-plus years,’ writes James Fallows, a China specialist, and asks: ‘What if China is going bad?’

Foreign businesses operating in the world’s second-largest market detect a more jingoistic and protectionist atmosphere. In a recent German Chamber of Commerce (GCC) survey, 37% of foreign investors felt that China had become ‘less welcoming’, with just 10% noting a more welcoming environment. In a similar survey of American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham) members, 77% felt less welcome.

As a result, companies are revisiting some political risk assumptions. President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption drive is increasingly seen as an excuse to weed out political opponents as he builds a personality cult. Corporate fears are compounded by the risk of a US-China trade war under President Trump. But others counter that Xi’s actions are an understandable response to public anger about official corruption, and foreign investors who observe the rules, argue the optimists, have little to fear. China is edging its way towards a market-oriented economy with legal and fiscal reforms that are closer to global norms. Indeed, given political uncertainty in the US and Europe, a relatively stable China might even be seen as the new free trade champion and pro-globalisation superpower.

Much investor unease stems from government efforts to reconcile short-term growth goals with long-term reforms. As well as Xi’s anti-corruption campaign, these include: supply-side structural reform to reduce overcapacity and debt; energy, healthcare and welfare reforms; changes to the hukou (household registration) system; fiscal improvement; a local government overhaul; infrastructure financing; and financial-sector liberalisation. Although welcomed by investors, the shift away from an investment- and energy-intensive growth strategy has been destabilising: in 2015, China suffered a stock market collapse and its slowest growth in a quarter century.

In response, policymakers reverted to previous growth drivers in 2016, relaxing restrictions on property investment and sanctioning another credit expansion. It seemed to work. GDP grew by a stronger than expected 6.7% year-on-year in 2016, within the government’s 6.5-6.7% target range, with the IMF forecasting to 6.5% growth in 2017.

Importantly, China’s service sector now accounts for some 64% of full-year GDP growth, according to Ning Jizhe, head of China’s National Bureau of Statistics, thanks in part to government efforts to rebalance the economy. China’s Markit/Caixin services purchasing managers’ index (PMI), hit a 17-month high of 53.4 in December. Although property-related services and purchases played a part, robust consumer confidence underpinned retail sales growth of 10.4% year-on year in the first 11 months of 2016. Online spending on 11 November ‘Singles Day’ (China’s ‘Black Friday’) hit a record $US17.8bn, compared with $US14.3bn in 2015 (and $US3.34bn on Black Friday in the US).

Consumer price growth has remained below the government’s 3% ceiling all year, while producer price inflation turned positive in October for the first time in four years. This suggests some progress in reducing overcapacity in key industries.

However, the creditable short-term performance has given rise to investor doubts about the government’s commitment to its long-term reform programme. Officials responded to these concerns in the fourth quarter by re-tightening property-related lending and other credit conditions. House prices then fell in first-tier cities and reversed in booming second-tier markets too.

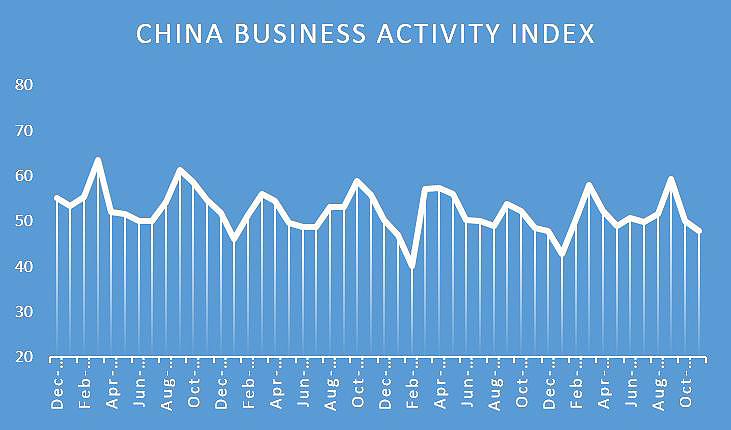

FT Confidential Research’s Business Activity Index fell 2.2 percentage points in November to 47.8, its lowest reading (outside of a holiday period) since the data series began in 2012:

Note: Index based on monthly surveys of freight carriers, exporters and real estate developers conducted by FT Confidential Research. January and February readings tend to be distorted by the Chinese New Year holiday, the timing of which varies from year to year.

SOURCE: FT CONFIDENTIAL RESEARCH

Leveling the playing field

The flux in economic policy is matched by regulatory confusion, especially at local level, where officials have been given leeway to implement centrally-set reform goals. Many are using this power to jockey for political advantage ahead of October’s 19th Party Congress, thus creating inconsistent, unpredictable and contradictory policy.

Rising labour costs are another investor bug bear. Nearly four fifths (79%) of GCC survey respondents—and 54% in the AmCham survey—cited this as a major operating problem, especially in wealthier coastal provinces. However, cooling economic growth and a shift to inland production is easing wage pressures. Data from Zhaopin.com, an online job site, shows average salaries of advertised jobs in Beijing (Rmb9,227 or $1,337) and Shanghai (Rmb8,664) are almost double those in struggling north-eastern cities such as Taiyuan and Harbin. Only nine of mainland China’s 32 provinces and municipalities raised their minimum wage rates in the first nine months of 2016 (compared with 21 that did so in the same period in 2015). And a growing pool of highly-skilled, often overseas-educated, local talent is offsetting the expat exodus of recent years. Furthermore, the government says it might relax China’s labour contract law that many investors say favours employees.

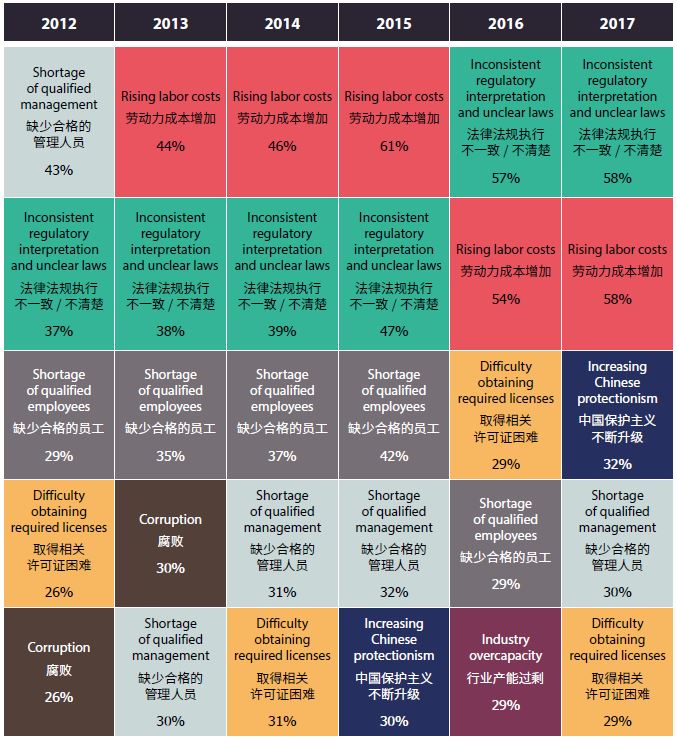

Regulatory favouritism more generally is a major gripe. Some 58% of AmCham members surveyed say that inconsistent interpretation and unclear laws are now their top challenges, up from 47% in 2015:

Top five business challenges for American Chamber of Commerce members

SOURCE: AMCHAM CHINA 2016 CHINA BUSINESS CLIMATE SURVEY REPORT

Many claim that local firms are able to dodge the rules, while foreign companies must be seen to abide by the letter of the law—and are pounced on if they fall short.

High-profile legal defeats have lead not just to fines or deportations, as in previous cases involving Avon and GSK, but imprisonment as in the case of Rio Tinto and Crown Resorts. China ‘is killing the chickens to scare the monkeys,’ says Dan Harris, a China-focused lawyer, citing a Chinese idiom, in response to the latter case, ‘The foreign companies are the chickens and the domestic Chinese companies are the monkeys.’

Chinese authorities deny targeting foreign business. Media coverage of court cases indicate that most anti-corruption or anti-monopoly rulings go against domestic groups. Furthermore, the legal system more generally is being nudged towards global norms. More anti-trust, patent and copyright infringement suits are being filed in China even when neither party is Chinese (such as Sony v WiLan), boosting the attractiveness of China’s legal system abroad. Investors hope that short-term disruption around reforms will eventually be worth it.

Many feel the same way about tax reform. The government is gradually replacing its business tax (levied on revenues) with VAT on a sector-by-sector basis. Despite increasing uncertainty, complexity and costs, the new tax rules aim to reduce the overall tax burden on business. Since May 2016, services, construction, finance, lifestyle and real estate companies have transferred to the new tax regime.

But the benefits will take time to accrue. According to a survey by the Unirule Institute, an independent Beijing-based think-tank, 63% of companies that have switched to the new VAT system reported a rising, not falling, tax bill as they struggle to obtain supplier invoices to reclaim VAT—an indicator, perhaps, of China’s large grey economy. Soon-to-be announced income tax reforms are expected to involve similar issues.

Cautious optimism

Despite mounting concerns, most foreign investors remain committed to China. Some 65% of GCC survey respondents expect rising turnover in 2017, while 52% expect profit growth—around 10 percentage points higher than a year ago. Almost all businesses surveyed see China as central to their global business strategies.

To be sure, some consumer goods makers, including Danone, Coca-Cola and Sony, are reportedly scaling back local production and selling stakes in Chinese joint ventures to local buyers. But these moves have more to do with shifting consumer preferences and market dynamics (such as growing demand for imported brands and rising labour costs) than overall market prospects.

Indeed, foreign direct investment grew by over 4% year on year in 2016 supported by a 52% increase from the US and 41% from the EU. Some 70% of the total was in services, with multinational tech companies such as Airbnb featuring prominently. For those foreign investors ready to take some short-term pain and uncertainty—which includes the vast majority—cautious optimism prevails.